Forget the exposure triangle! A simpler way to understand exposure.

I’ve gone into depth on how to use a real exposure triangle, but there’s a much simpler way of than thinking in triangles:

FORGET ABOUT ISO

What?!

Here is the deal, ISO just gets in the way. And it doesn’t provide a creative effect when changed. Now we can go from juggling three relationships to just one: shutter speed versus aperture. Using a familiar and constant ISO is like finding middle-C on a piano or the bumps on the 'f' and 'j' keys on a computer keyboard.

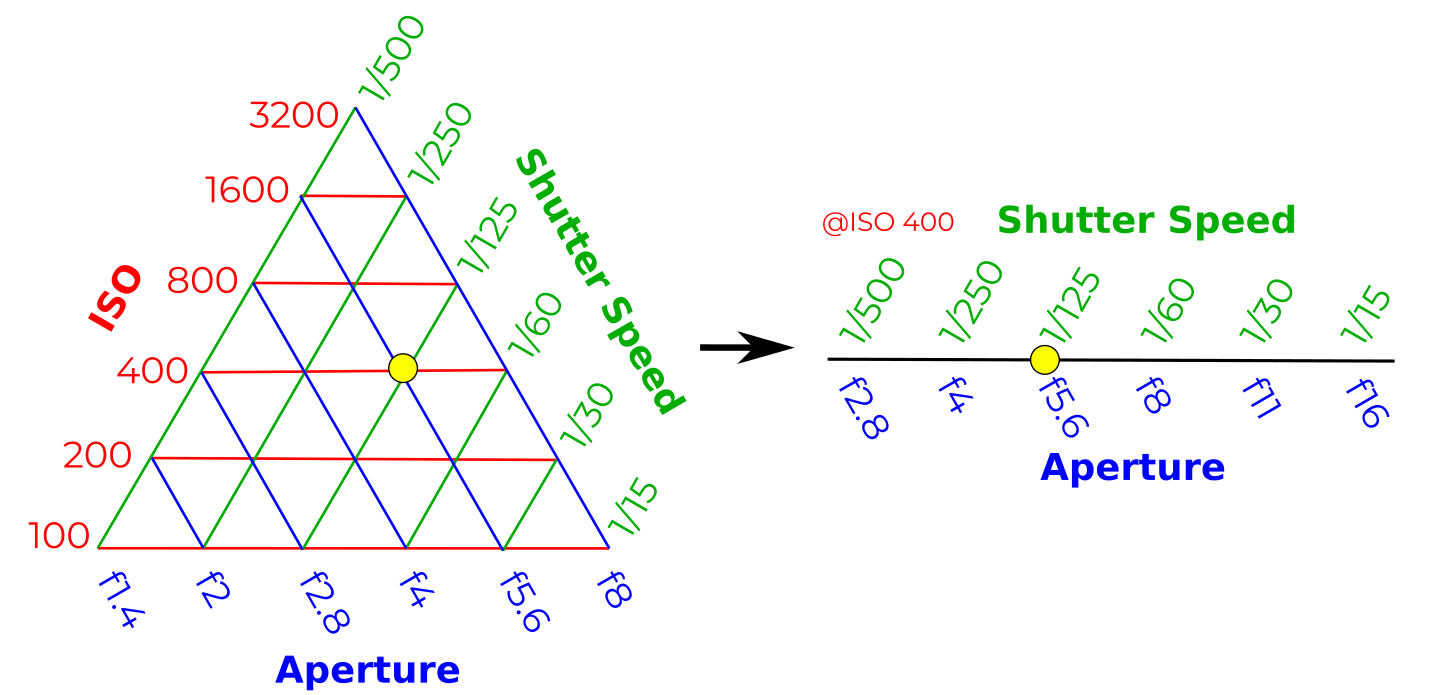

The figure below shows a triangle with an example exposure of ISO 400, f5.6 at 1/125th of a second. If we always shoot at ISO 400 we can simplify to a line where all we need to know is f5.6 at 1/125th. All pairs of values give the same resultant exposure, so f4 at 1/250th = f5.6 at 1/125th = f8 at 1/60th.

We can lighten exposure by shifting the aperture values to the right (e.g. f4 at 1/125th), or darken by moving them to the left (e.g. f16 at 1/125th).

Take ISO out of the equation, and you only need to worry about the creative variables of shutter speed and aperture

You can take ISO out of the equation two ways. (1) You can act like a film shooter with a fixed speed like 400 and make it work in both dim and bright conditions (or use a limited palate of ISOs like 100 for sunny conditions and 800 for indoors) or (2) There is the possibility of ‘auto-ISO’ on digital cameras. This can make life easier in rapidly changing conditions, but in more stable conditions, a fixed ISO will prevent the camera’s meter from getting fooled by light or dark elements in the frame.

Now the ISO is removed from the equation, we can just worry about aperture and shutter speed, which both can control the amount of light and provide some creative decisions for your image. Using this information and locking-in ISO400 I can use 1/500th at f16 outdoors on a sunny day, or 1/60th f2 indoors on an evening. If conditions get slightly darker or lighter, the shutter speed can be raised or lowered a stop or two. Doesn’t have to be a perfect guess either. Film is very forgiving of incorrect exposures and it’s not really a problem for digital cameras anymore also. All this said, with a simpler way to estimate exposure, your guesses will become very accurate very quickly.

Of course there are always exceptions to rules of thumb, so you might want to return to ISO variations if you want to use extreme shutter speeds or apertures.

Single exposure, many shutter/aperture combinations

There are equivalent shutter/aperture combinations, known as reciprocals that result in the same resultant exposure.

A great way to see reciprocals in action is on an old Hasselblad lens - exposure is determined as an 'exposure value' (EVs) - a single number which represents all equivalent shutter/aperture combinations assuming a fixed ISO. EVs can be determined on light meters such as the Sekonic 758. On the lens, the shutter speeds and aperture value rings are locked - meaning that if you want to get a faster shutter or decrease depth of field, you can do so without changing the amount of light hitting the film.

Digital cameras won't let you set exposure this easily. P mode almost does it, but it re-calculates for every picture. It would be great to use one control wheel to scroll through EVs, and another to pick the desired combination.

exposure variables quick reference

It’s useful to think in full stops (doubling and halving of light values) to further simplify the process. Half stops are overkill for most types of photography and third or tenth stops are for precise scientific, studio and product photography. For most people, using less than full stops are an illusion of precision that is not important for your images.

Shutter Speed

Slow shutter speeds (e.g. 1/15th, 1/30th) let in lots of light, but any movement of camera or subject might cause motion blur

Fast shutter speeds (e.g. 1/250th, 1/500th) doesn’t allow as much light to the sensor, but can freeze motion

Full stop speeds: 1s, 1/2s, 1/4s, 1/8s, 1/15th, 1/30th, 1/60th, 1/125th, 1/250th, 1/500th, 1/1000th.

Aperture

Wide apertures (e.g. f1.4, f2) have a narrow depth of field (blurred background) and lets in a lot of light

Narrow apertures (e.g. f11, f16) have a wide depth of field (lots in focus) and restricts light to the sensor

Full stop apertures: f1, f1.4, f2, f4, f5.6, f8, f11, f16, f22, f32

ISO

Low ISOs (e.g. 100, 200) are for high light levels and have minimal digital noise/film grain

High ISOs (e.g. 1600, 3200) are for low light conditions at the expense of more digital noise/film grain

Full stop ISOs: 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200, 6400